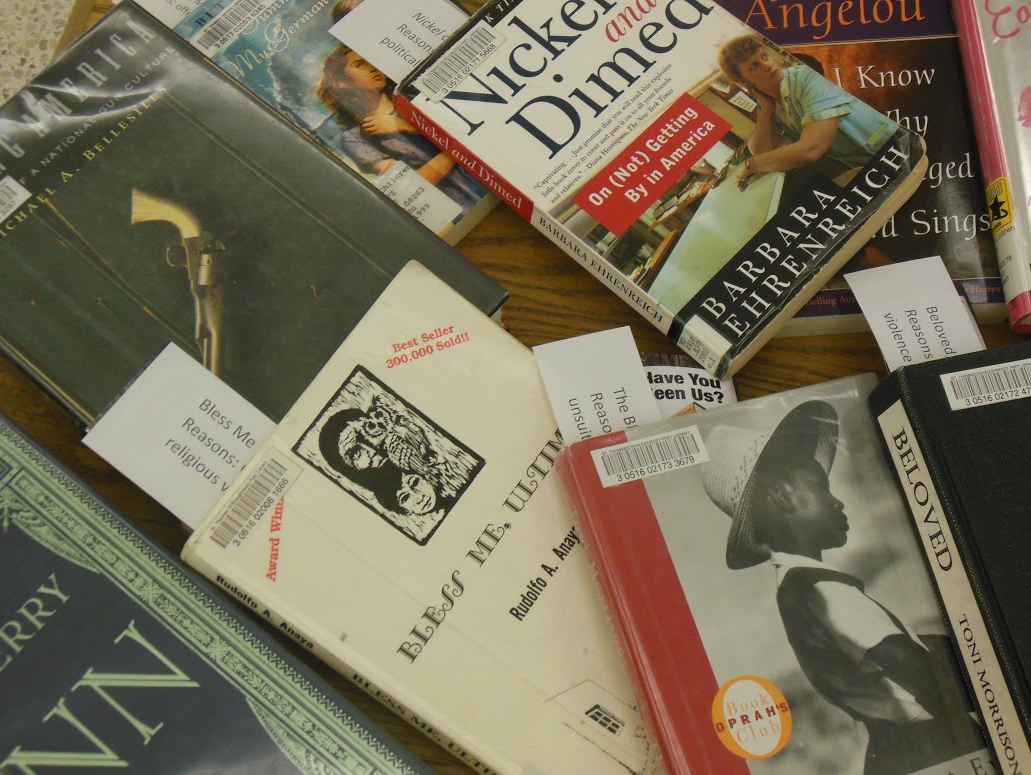

In cities and towns across the U.S., books are selected and stripped from the shelves. Books are challenged, and their message is questioned before they are eventually banned and removed from circulation indefinitely.

No, this isn’t a scene from “Fahrenheit 451.” It’s the common process by which books have been challenged and banned at schools and libraries across the country.

For more than a century, books have been subject to challenges and bans in libraries across the country. Since 1990, books ranging from “The Jungle” and “The Great Gatsby” to “The Hunger Games” and the Harry Potter series have been challenged in U.S. schools and libraries.

To raise awareness of banning and challenging books throughout history, the O’Shaughnessy-Frey Library marked the 32nd annual National Banned Books Week by setting up displays and posting daily trivia questions on its website.

According to Andrea Koeppe, research and instruction librarian, children’s and young adults’ books are the most commonly challenged and banned materials, but she doesn’t necessarily agree with those actions.

“It’s well within your right to expect that someone wants to protect their kid from ideas that they may not agree with,” Koeppe said. “However, I think it really oversteps a boundary. You know, you can protect your family. If you don’t want your kid to read ‘Tango Makes Three’ or ‘The Hunger Games’ that’s fine, but I think it violates every principle of free speech if you tell me that I can’t let my son read those books.”

Freshman Krystal Hoang, a trivia winner, said she believes people have the right to choose what they want to read.

“If someone doesn’t like the book, he or she can hate it as much as they want and make critiques; but that is not a good reason to stop everyone else from reading it,” Hoang said.

Banning a book doesn’t mean that it’s completely unavailable to readers. A book is first challenged, which means there is an attempt to remove it from a certain library based on objections from an individual or group. If the challenge is successful, the book is then banned from that library. Readers can still get the book at other libraries that have not yet banned it.

According to Koeppe, violence, sexual content and unsuitability to age groups are the three main reasons parents give for challenging books.

“(Parents) maybe don’t want their kids to read about two gay penguins like ‘Tango Makes Three,’ or they don’t want to read about teenage suicide or teenagers killing each other a la ‘The Hunger Games,’” Koeppe said. “And I get it. I mean, it comes from a good place.”

Hoang said she was surprised to see “The Hunger Games” on the banned book list.

“It’s a good book, and people can learn from the themes in the book,” Hoang said.

The O’Shaughnessy-Frey Library was just one of hundreds of libraries across the U.S. celebrating Banned Books Week, which ran from Sept. 21 to 27.

“St. Thomas (has) been commemorating it for – at the very, very least – 10 years,” Koeppe said. “We’ve had some speakers some years. Our goal is … to raise awareness.”

Although the library’s slogan for the week is “read a challenged or banned book,” Koeppe doesn’t want to force students to read any books that they don’t want to. She would like students to realize that book banning still goes on today; and in the end, she said she hopes the week’s celebration will encourage more dialogue about books.

“More conversation is better than less conversation,” Koeppe said.

Theresa Bourke can be reached at bour5445@stthomas.edu.