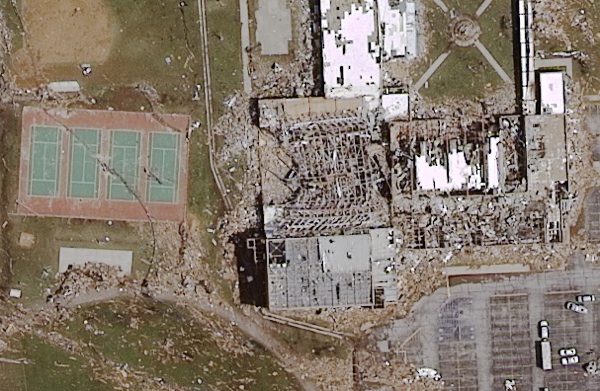

JOPLIN, Mo. — The twister that laid waste to much of Joplin last month hit the school system especially hard: It killed seven students and one teacher and destroyed three school buildings, including the only public high school. Seven other buildings were badly damaged.

Now officials are trying to put the crippled district back in order, with only a couple of months to get everything working again before the fall term begins. Many classes will have to meet in vacant buildings. There are also computers to order, furniture to replace, water-logged lesson plans to rewrite — even dirt-encrusted books to salvage.

And the effort goes beyond accommodating students and teachers. In the aftermath, the resurrection of Joplin High and other public schools has become a rallying point for the whole community.

At the debris pile that used to be the high school, someone used duct tape to turn a sign missing all but two letters from “OP” into “”HOPE.” In front of that sign are three wooden eagles — the school mascot — carved by a Tennessee artist from the remnants of oak trees that were sliced in two and stripped of their bark by the nation’s deadliest single tornado in six decades.

“Her feathers are ruffled, but she’s not dead,” reads a nearby spray-painted, cardboard sign.

Barely three weeks after the storm, summer school began last week. More than 1,600 elementary school students alone enrolled — almost double the number from last year. The district added an extra month of classes for a session that was initially scheduled to end in early July. And unlike previous years, it’s offering free transportation.

“These children don’t have a home to live in,” said Irving Elementary School Principal Debbie Fort, whose school was one of those destroyed. “Parents know they need to get a routine back. Their lives have been turned upside-down.”

Because so many buildings were damaged or destroyed, half of the high school students will attend classes in an empty big-box store. Many middle school kids will go to a vacant warehouse in a far-flung industrial park. Some administrators will take over an old office of the state transportation department.

Signs of the tornado are visible even in schools that escaped any damage. At Stapleton Elementary, boxes of library books rescued from damaged buildings sit piled outside the main office. A 7-year-old boy matter-of-factly explains to a visitor why he’s on crutches — a piece of wooden shrapnel pierced his calf, requiring emergency surgery and a week in the hospital.

The twister killed more than 150 people. Immediately after the storm, Fort searched for missing teachers. Even now, two displaced families, including one of her faculty members, are staying at her home in nearby Webb City.

Yet for the most part, the rhythm of the school day is unchanged. For many students, the classroom offers a respite from troubles at home.

“The kids are just relieved to be back at something peaceful,” teacher Isaiah Basye said. “It gives them hope, to see that we’re not letting the tornado change us. We’re still here with open arms. This place is a haven.”

The tornado forced school officials to end the spring term nine days early. Administrators have promised that fall classes will begin on time Aug. 17, and they have found alternate sites for each of the damaged or destroyed buildings.

At Junge Field, the high school football team has started practice. Its stadium was unharmed, but its practice field and weight room were both a total loss. One team member remains hospitalized. Others have yet to return after they were scattered to temporary living arrangements with friends or faraway relatives.

New coach Chris Shields lost the rental home into which he had moved some belongings even before relocating to Joplin from suburban St. Louis. Seventy students attended the first day of practice, fewer than the 85 he expected.

“When your home is destroyed, football is not always your top priority,” Shields said.

Defensive end Jarad Bader said he and his teammates feel an added sense of responsibility to represent Joplin on Friday nights this fall.

“We don’t really feel like we need to say, ‘Win for Joplin,'” he said. “We know inside that Joplin is helping us. It’s time for us to help Joplin.”

Said free safety Evan Wilson: “It’s kind of understood. We have a lot of weight on our shoulders.”

With the loss of Joplin High, which served 2,200 students, school leaders say they want to do more than merely rebuild. They envision a state-of-the-art structure that could establish Joplin not as a district scarred by disaster but as a center of innovation.

School administrators invited a panel of education leaders to a wide-ranging discussion of how the new Joplin High can emerge better than ever. Among the goals: more one-on-one learning and increased collaboration with the adjacent Franklin Technology Center, a vocational training site that was also destroyed.

“We need to let ourselves be free to dream,” Assistant Superintendent Angie Besendorfer said. “It’s really hard. We’re living with the reality of what happened. You almost have to give yourself permission to move past the really horrible, horrific things.”

Those discussions were already taking place before the tornado, Besendorfer said. But now they have moved from hypothetical to urgent.

“This tornado accelerated that process — in about 45 seconds,” she said. “We had already dreamt about ‘what if?’ Now, it’s very much ‘what’s next?’ ”